Critics are saying there are too many people with access to classified information – but is that really the case? And when it comes to leaks, is creating fewer individuals who are close to classified information – but not vetted to see it – really the solution? ClearanceJobs interviewed Charles Phalen, former acting director of the Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency (DCSA), and current principal of CS Phalen & Associates. They discuss why personnel vetting is scrutinized following every major leak, why cutting the number of security clearances seems like a plausible solution (but isn’t), and eApp and possible changes to the security clearance application process.

Lindy Kyzer:

Hi, this is Lindy Kyzer with ClearanceJobs.com, and welcome. Every time we have this show, I feel like we’re talking about security clearance topics in the news, and that’s certainly the case now as we are unpacking some legislation that was currently announced out of the Senate related to reforming the security clearance process. No surprise there. It’s been a topic that’s been talked about, and we’ve kind of known that the Senate was looking into this since the release of classified documents, the sloppy security practices, perhaps, that led to classified documents being found at Mar-a-Lago, the home of vice president, then Joe Biden, I think even Mike Pence at some point. It was actually cool to start talking about how that you had classified documents at your home.

So, in that vein, I wanted to ask one of my favorite experts on the security clearance process, on personnel vetting specifically, and who has really given some great insights into the number of security clearance holders in the past, which is, again, a topic that I’ve seen in the news, and that’s Charles Phalen. He is the former acting director of the Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency, now with CS Phalen Associates. You will see him all around the security clearance community providing his insights into everything from insider threat to, again, personnel vetting reform, which is the topic I asked him to address today. So, thank you so much, Charlie, for being on the show and for chatting with me. I really appreciate it.

Charles Phalen:

Very happy to be here today.

Lindy Kyzer:

We’re kind of talking about the Senate and the legislation that was proposed. The messaging from the Senate over the past month, ever since the Jake Teixeira case, has really centered around how many people have a security clearance. The fact that a young person had a security clearance I heard, which I definitely was kind of surprised that that was the line of criticism, but it’s not a new line of attack. You came to mind right away because I know you’ve testified before the Senate Intelligence Committee on this very fact about the personnel vetting process and the number of security clearances. So why do you think that the number of security clearances is one of those things that the Senate really hits on when they’re looking at security clearance reform, which is an ongoing topic for them?

Charles Phalen:

Good question, and my instant reaction to this is, is this another case of round up the usual suspects, that this is an easy target? And just go back to what we always go back, and ask, “So, how many people have clearances, how many people can get access to it?” And the other part of it, the legislation is not only looking at the clearances but at the vetting process itself and looking for flaws in that. But getting to the current events, the number of cleared people is an interesting number. We can talk a little bit more about that later, but this is in fact the actions of one person as to the process before questioning the process as a whole, which some people will probably want to do. First, they got to do all the forensics to see how this all happened. And a big move in the clearance processing in the last few years has been the move to continuous vetting.

So, once the person has been deemed as eligible for access to classified information, to have a near real-time capability of understanding whether that individual has changed in their behaviors or whatever, so one can make real-time reporting and then make a more near realtime determination about continued eligibility. This does place an obligation, not an option, an obligation on officials, on managers to report aberrant behavior, things that are strange, things that are odd. The media has reported on at least three occasions, Mr. Teixeira was seen to be looking at information that he really should not have been looking at. And some officials knew about this, but my question would be, and I have no inside information on this, “Was this reported to an insider threat hub of any sort for them to take actions?” This apparently occurred, again, based on media reports, at least three times over the previous six months before his arrest.

So, I would argue maybe don’t beat up on the process so much. There was a clear path to report this information. If that was not taken, that’s the problem. There’s a process that’ll deal with it, but the process has to know that there’s something to deal with. So again, I think it’s less about the total number and more about are people following a process that’s been put in place to find this stuff.

Lindy Kyzer:

I agree with that line of thought. I’m always coming at it from the side of the hiring and recruiting market where we just find that that’s the opposite case. Where we have a finite cleared talent pool and a number of folks in the population, exactly like you said, when you have an issue with one person, to kind of attack the number of security clearance holders does seem to miss the mark a little bit. There’s a lot more to the Sensible Classification Act and the Classification Reform Act than we’ll be able to unpack here. Not all of it is bad. I think I’m taking the critic’s angle, but it does address overclassification, declassification reform, and that’s not my bread and butter issue. So, I don’t know when those topics have been reformed, but kind of the drum I’ve been beating is saying, “Hey, let’s look at policies through the IC or through other things.”

Why do we always have to hit vetting over the head when an incident happens? But I am calling out Section 9 of that Sensible Classification Act because it requires agencies to report on the number of secret and top-secret security clearances. And it directly ties into, again, the messaging line that’s been coming out of Congress. One senator has called the number of people with security clearances crazy. There’s just been a lot of criticism of the number, and the legislation asks agencies to reduce the number of clearances where possible. I push back: What if they need to increase the number of clearances or billet? Why isn’t that in the legislation? So, can you kind of talk to why reducing the number is the focus and why the legislation would point to that?

Charles Phalen:

Looking at the number of people cleared, is there something easy to focus on? But the real question is, what impact would reducing the numbers actually have? The starting point here is, I’m pretty sure that the cleared community, whether it’s the intelligence community or the Department of Defense or whatever, has those numbers. And I believe, unless things have changed considerably in the last couple of years, they report these numbers, and they’re available to Congress as to what the numbers of folks in each categories are.

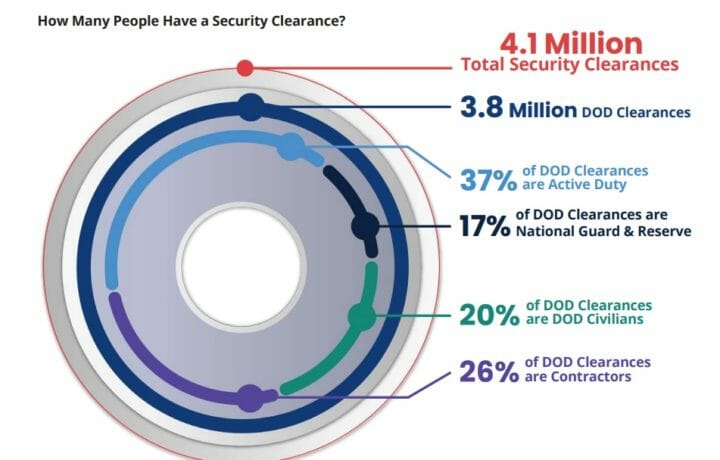

I don’t believe that the reduction of people in the classified world is going to have any particularly great impact on this. Whether there are 4 million people cleared, which is a round number that is used today and thrown out on the table, or 3 million people cleared, or two and a half million people cleared, that’s an awful lot of people that we have made trust determinations on. In all cases in the old days or today, the question of who gets a clearance is based on a need to either have information or be in proximity of things that are sensitive, and that means there needs to be trust in the role that they are performing.

Some people, think of your average intel analyst, are up to their ears in classified information, and in fact, the amount of information that they can see now is just huge because as we moved into the computer age, rather than every document being stuck in the safe somewhere, it gets pushed out to people that need to use it along that supply chain. Some people will only occasionally come across this sort of stuff, and in particular, that would be folks that are in oversight processes, whether it is a industrial general council or the CEO of a company or somebody, or others that are just in leadership roles but don’t have to see every day, every piece of information. Some of it is just being in proximity to the classified information. For example, IT technicians, like Mr. Teixeira, this trust determination was made on them because they’re going to be in and around and assembling systems that are handling this highly sensitive information.

My question would be: “Do we want to have more trust or less trust in these people?” Or more trust in people, as they work around this sort of thing. I would ask the question, for example, if somebody’s putting together the highly classified IT system, do you want to know whether you can trust them to do it right and whether they’re going to compromise this thing? Do you care how much you trust the individual who is assembling the navigation system on the new B-21 bomber? I think the answer those two questions is absolutely yes.

And then, one thing that is not addressed in these is because this is an intelligence community draft that is going out as opposed to other parts of the Senate. Is the suitability and public trust side of things where actually DCSA is doing the investigations to make sure that to inform agencies about the potential for suitability issues or public trust issues, for people that are going into sensitive positions, not access to classified information, but access to some fairly sensitive information. As we move along in this integration of classified world and the trusted population that is not classified through the PAC PMO, they’re moving more of these processes together to work more closely in parallel, and that line is going to get more and more blurred.

I think this is actually a good thing because trust is trust, and in the end, “Can I trust you? is the most important question. So, the real question to be answered in all this, I’m getting sort of off the topic here, but the real question to be answered in all this is not so much how many cleared people do you have, but how well and how do you control the information designation? That would be the classification determination, whether something is or is not something to be protected, and perhaps more importantly, how do you control the flow, which it has been a flood ever since IT systems were set up.

And the amount of information that moves through these systems to various points on the compass just gets greater and greater every day. And my experience is it’s not entirely clear to the people who are putting information into these systems that they even know where it’s going to. So, that is, I think, the flow of the information, how that gets controlled is perhaps more relevant in this case than it is whether there’s three, four, or 2 million people cleared in the government.

Lindy Kyzer:

I love that you pointed out the suitability in public trust aspect because that’s something we’ve been kind of prepping for in terms of messaging and thinking there needs to be more information going out to that workforce about what that scenario looks like. But rolling out Trusted Workforce 2.0 to the entire federal government population will be enrolling a lot more people into a vetting scenario.

To your point, I think is a good thing. Again, do you want people that you can trust working in the government? But I think you could see more of these issues spiraling out if you find negative news because there are obviously folks that have PIV card credentials and other things that happen that are going to get flagged under a CV program for issues. And that’s a good thing.

That doesn’t mean our workforce is bad, it means the system is addressing issues sooner and we’re able to vet people in a better way and provide help to the workforce I think in good ways. But I think what you could see is, again, just more criticism of the government and federal population, which is, again, the opposite of what we need right now. I think we need more people to pursue careers in national security, more people who want to work for the government. And when you kind of attack the workforce around these issues, I think it’s going to have a negative impact.

Charles Phalen:

I would agree with that Lindy. And you think about where this is going to. The notion of a continuous vetting program is to see problems, challenges, trust challenges occurring much earlier in the process than you would in the past. And so, what that enables, and in my experience, is people don’t wake up one morning with being perfectly fine the last 10 years and say, “I’m going to betray my country this morning.” Things degenerate over time.

The sooner that an organization, an element can see that somebody’s going off those tracks, the sooner they can address that issue and make one of two decisions. One is help get them back on the track. And my experience has been a lot of people are able to get back on the track because the mistakes they’re making have been, I don’t want to say innocent, but have not been intentional. And get them back on the track and get them back into a full trust capacity. Or make that determination that they’ve gone too far and we can’t trust them, and don’t want to wait until something really bad has happened.

Lindy Kyzer:

Absolutely. And then, the SF-86 always comes up that, again, because it’s a key aspect of the vetting process. I find it’s interesting that a ton of people are criticizing saying, “Hey, we need to update the SF 86.” And I’m like, “Come on, don’t you read ClearanceJobs.com?” So, they already have the PVQ, they’ve already released proposed changes. There was an open comment period for those changes. So, I’ve not seen the final version of the PVQ, I’ve seen the draft of the PVQ. Do you think there’s going to be more pushback now to change the form? Is that something the government’s going to look at in the wake of all of this, or do you even think that that’s a necessary step?

Charles Phalen:

This particular event or events like it doesn’t lend itself to saying, “Hey, you need to change the form.” I mean, there is no specific question in the form that says, “Hey, are you playing games out there with your friends and giving them classified information?” But it does go to the question of trust. I don’t see this Teixeira case leading to something changing on the form itself. But there are, and legitimately have been questions raised in the past about do you need to bring the form and the form of the questions and the way they’re addressed somewhere into the early 21st century as opposed to the late 1950s when these things were first put out? And two areas that keep popping up. One is a current event area, the other is a long-running one. We’ll take that one first, and that is the whole issue of mental health.

The original question 21, and I’m pleased to see that that question has been revised, that the focus is on clarity, on simplicity of it as opposed to the old question 21, which can take you off into literally a dark hole sometimes. It’s created stigmas and discourage people from getting treatment that they needed for things that are easily treatable and easily something to be taken care of, and something that people really shouldn’t try to, or feel like they have to hide. If you’re struggling with some things, get it fixed.

I think that’s a big change in the positive direction. The other one is some idea that if we rephrase the questions, then we’ll get quicker to understanding whether there is, in more current term, whether there is domestic violent extremism in the veins of the individual that is applying for a clearance. And the emphasis here, in my view, is on the violent part, I think there’s enough leeway in the way the questions were asked and things that could be explored that you could get into whether somebody has a violent history or violent aspirations.

And as people start to look at, it starts to end up looking a little more political in terms of the way the questions might get asked. So, I would say they don’t need to really rephrase that a whole lot, focus on violence, focus on that sort of stuff. Don’t try to politicize it at all, but we’ll see where that one goes. And I haven’t seen the most recent updated version of the new PVQ, but we’ll see where that goes. I would say there’s one interesting aspect of this thing, which will have to happen regardless of what they do with the new form, but folks have just gone to a lot of work to refigure the e-QIP into eApp, which is online, and those of you who haven’t used eApp, I have, I find it to be a full century better than e-QIP and much easier to use and I’m thrilled with the way that turned out.

With a new PVQ, they’re going to have to do some recoding, so it’ll be interesting to see how they can get it recoded, and more importantly, how they can link up the various parts of the E-app that people have already filled out, back into a new version of a PVQ. But that’s for the techs to figure out.

Lindy Kyzer:

Yeah, the century remark is absolutely true when it comes to e-QIP to eApp. When it comes to the PVQ, I feel like it’s great that you kind of correlate those because a lot of the changes are just in how the information is set up and how the forms are split out. So, that will be a coding issue for how those are set up. And it does ask more questions about, I know, handling protected information and kind of tries to unpack that question a little bit about trustworthiness around data protection, which again, the issue with the Teixeira case is, like you said, he had a background documented at least based on the news reports of already mishandling classified information. So, that should have been the red flag issue prior to any leaks on Discord. But I will tie that into my next question, which was about social media.

So, the big hit I’m seeing, beyond, “Hey, there’s too many people with security clearances around the vetting process,” is, “Hey, why aren’t we using social media as a part of that process?” My pushback is, even if you’re looking at social media, how are you going to find private information through password-protected servers on a place like Discord? A lot of things can happen on the deep dark web that are not going to come up through a background investigator’s time. But I’d be curious, based on your vetting expertise, obviously working in the intel space this long, we know that social media can be a factor in the security clearance process. Cyber vetting is baked into policy. We can use it, but do you agree with criticism that we need to be using more social media? That we need to be asking people for usernames and handles and passwords, which I’ve also seen. Talk about the social media piece of this a little bit.

Charles Phalen:

Yes, I think there’s broader possibilities that can be explored and used with social media, but to your point, I mean, there are different thoughts on the application. My view on this, based on seeing a lot of this stuff in the last few years, the best use of it is if I’m following leads, from say, a CV lead or something, so if Teixeira is doing stuff online, and somebody says that to us, then going through publicly available sources can be very useful for clarification, for validation, maybe to refute certain things in a specific, let’s follow the lead and follow the message here.

What I’ve found is, it is not so effective as a screening tool. In the trials that were run in a couple of my earlier lives, we went across the publicly available information. We would look through a number of applications, a number of applicants, and scraped everything that could be scraped on these individuals. Frankly, the volume of information that was coming back worse, the ambiguity, is it really John Smith or some other John Smith, questions about the validity.

There was very little that came out that said, “Here’s something that is useful to follow.” And maybe as we get into, this is the big ticket thing these days, get into more AI applications, maybe there’s some way of using AI to look at these sort of… Take from some of these screening tools and say, “Can they do a better job and a quicker job of disambiguating all this stuff and perhaps validating or not refuting it, to then hand it to a human to help make that adjudicated decision over a particular fact or something?”

I think that’s probably worth exploring at this point. But to your second question, the question of the boundary, we’ve all agreed collectively that open source information, publicly available information, is fair game. Put it out there on public sourcing, and it’s out there. I think I have a different opinion on whether we can routinely demand access to people’s private accounts, whether it’s their personal Facebook account or their personal emails, or into their gaming accounts, whatever, and ask them to give us access to these sort of things. With a search warrant, particularly with some probable cause, I think that makes perfect sense.

But as a routine thing, I think I would rephrase the question. How do you feel about DCSA, using an example, being able to listen to all of your phone calls or put a microphone in your family room and listen to all those conversations that are taking place. I just don’t think that’s appropriate in this country today. So, in my view, the boundary is open source versus getting routine access in people’s passwords without some kind of due cause.

Lindy Kyzer:

No, I absolutely concur. And again, I feel like what these cases generally show is there usually is some external information outside of the vetting process that showed the red flag issues, but they just kind of… We go to the beginning in the story rather than hitting where the issue should have been caught because it’s a lot harder to address the insider threat issue, the leadership, the command culture, company culture, or just community around how information is protected.

But vetting, we know the process. It’s governed in a lot of policy, so we just tend to hit that a little bit more. But I would like to see a little bit more look into how these things actually happen and the buildup, and maybe some better case studies around why are we kind of allowing somebody to mishandle classified information and still retain that access. I’m not sure. Is there anything else that I didn’t address or we didn’t unpack here that you wanted to make sure we discussed?

Charles Phalen:

Well, couple things. One of the other parts of the messages you talked about or legislation that was proposed has to do with classification and declassification handling. Short answer on that, it’s hard. There’s a lot of information out there that is sensitive and needs protection. In fact, the creation of controlled unclassified information is recognition that it doesn’t just stop at declassified/unclassified realm. There is this gray area of needs-to-be-protected government information.

And frankly, the same goes for a lot of company proprietary information. And all of this stuff fits into some tactical or strategic framework. All of it is something that is designed or defines as gives us, whoever “us” is, the government, the company, whatever, an edge over competition. The other side of that coin is that competitors, whether they are nations or other companies, will take everything they can get their hands on, and the volume of things that have to be put into these categories is, and will continue to get, larger and larger.

The key to this whole thing, again, is control: control of the information. We’re talking about 4 million people that are cleared and trusted in this country right now. They don’t need to see everything. How do we, as a government, how do we, as whatever, control the pushing out of that information and yet the same time make sure it doesn’t go too far here.

And we’re still struggling with, sort of post-9/11, actually post-global war, whatever it was, back in 1991 where we needed to push that information to warfighters and people who needed it. But now it’s being pushed out without a whole lot of regards to where it’s going. And we need a more sensible distribution system, I think, rather than worrying about whether it needs to be classified or not. It still needs to be a process for classification, but it is really how do we control the movement of it.

Lindy Kyzer:

I know it is a part of the current Senate reform, and the proposals is looking into those classification processes. So, I hope that gets some of the questions and some of the scrutiny. But thank you so much, Charlie. As always, I appreciate your insights and your expertise, and your continued giving back to this security community that you’ve been a part of for so long. I appreciate it.