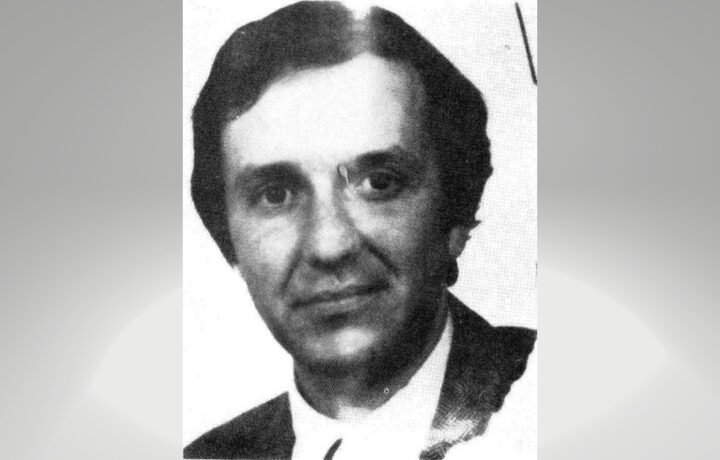

If ever there was an ignoble story of a former employee of the Central Intelligence Agency, dismissed from service for cause, the story of Edward Lee Howard fits the bill. On this date, July 12, 2002, Howard died at his home located in the Moscow metro area. The cause of death: broken neck from falling down a flight of stairs.

Howard, using the skills taught to him by both the FBI and CIA, eluded the FBI’s surveillance and successfully defected to Russia in 1985. He brought with him the knowledge of both CIA human and technical operations, but for the next 17 years he remained a “guest of the state.”

David Wise wrote a book about Howard, “The spy who got away: The inside story of Edward Lee Howard, the man who betrayed his country’s secrets and escaped to Moscow”, and the CIA archives includes a 7-page New Yorker magazine excerpt, also written by Wise which provides a detailed description of his use of the tradecraft he was taught for his anticipated assignment to Moscow, which he and his wife used to affect his escape from their New Mexico home and his circuitous travel route to Moscow.

Howard’s employment terminated

From 1981-1983 Howard was a CIA employee, he had been selected for assignment in Moscow and as is routine prior to sensitive assignments was administered a polygraph (March 1983). During such, he admitted to a transgression involving petty theft. The CIA determined he lacked the suitability and judgement for the Moscow assignment and not only canceled the assignment, but they also terminated his employment in May 1983. Following termination (resignation), Howard left the Washington D.C. area and moved to New Mexico. The CIA assisted him in finding employment in New Mexico.

Nevertheless, his life spiraled downward. In February 1984, he was involved in a drunken brawl in New Mexico and pulled a sidearm which landed him in jail for “assault with a deadly weapon.” He had hit rock bottom.

Howard phone calls to U.S. Embassy Moscow

In early 1984 Howard began making open line phone calls to the U.S. Embassy in Moscow switchboard. From the Embassy side of the equation, they were coming across as “drunk dialing.” He asked to speak to individuals whom he knew at the Embassy, the senior-most Soviet citizen employed at the Embassy, and the Chief of Station. The switchboard operators (Soviet citizens) and those with whom he connected all reported the calls to Embassy personnel. From the Moscow Embassy optic, his calls became increasingly more and more detailed as to the level of his disgruntlement with the CIA.

Those at the CIA knew he had been prepared to handle sensitive assets in Moscow to include Adolf Tolkachev (the billion dollar spy). He was also made aware of a significant technical operation targeting the Soviet nuclear research. The CIA engaged Howard, offered him counseling, which he considered (based on post-defection interviews) to be more about “limiting my potential damage to the CIA than in helping me.” Howard also noted he made the call to the CIA Station Chief “deliberately and in anger.”

There was good cause for the CIA to be worried.

KGB defector Yurchenko turns on the lights

In August 1985, Vitaly Yurchenko, a Soviet KGB officer defected to the United States, and as part of his bonafides, he provided information about Soviet intelligence operations involving the United States. Yurchenko identified to U.S. intelligence that a former CIA officer had approached the KGB in Austria and had been given the codename “Robert.” The tidbits provided included:

- Robert was CIA and had been slated for assignment to Moscow

- Robert traveled to Austria in the fall of 1984

Ironically, one of the CIA officers present at the debriefing of Yurchenko was none other than Aldrich Ames who was at that time providing the Soviet KGB information on CIA operations and sensitive Soviet intelligence sources. Howard and his spouse had visited Austria in September 1984. In early-1985, Howard made a second trip and returned to New Mexico with a new Rolex, Swiss gold coins, and (inexplicably) Russian hats.

Confrontation and escape from New Mexico

In September 1985, the FBI confronted Howard in New Mexico and put him under surveillance. Howard, trained in the art of surveillance detection by both the FBI and CIA, detected the surveillance. Howard approached a member of the surveillance team and told him “I am ready to talk” and explained he would get a lawyer and meet the following week.

The next night, he and his wife Mary went out for dinner, and Howard wasn’t seen again until he was acknowledged as being in Moscow.

On the way home from the dinner, the couple utilized the “jack-in-the-box” escape technique where he jumped from the car while Mary drove through a blind spot in surveillance, and she put a dummy up in his place. Trailing surveillance saw nothing. She drove the vehicle into the garage and then called a number which she knew would be answered by an answering machine and played a pre-recorded tape of Howard’s voice. The couple bought Howard escape time. The FBI saw the couple return home and technical surveillance heard the phone call.

Howard for his part made his way to Albuquerque, caught a flight to New York, and then onward to Helsinki. He walked into the Soviet Embassy in Helsinki and was whisked across the Finnish/Soviet border and then onward to Moscow. On August 7, 1986, he was granted political asylum.

Howard’s life in Moscow devolves

Many a stone loses their luster over time, and such was the case with Howard. In 1985 when he arrived in Moscow, he had minimal knowledge, and in hindsight, it was largely confirmatory to that which was being provided by Ames and Hanssen.

Howard was nonetheless rewarded. He was provided an apartment in Moscow and a dacha in the community of Zhukovka, as well as a monthly allowance. His alcohol abuse came with him.

By 1991, the Russians were merely tolerating him. He was of minimal value and was no longer afforded protection. He had devolved to being but a footnote in espionage history.