National laboratories have a reputation for being vulnerable to penetration by foreign intelligence. The Government Accountability Office certainly thinks so, anyway. Earlier this year, the congressional watchdog roasted the Department of Energy for its failure to fully implement the Insider Threat Program, the U.S. government initiative to counteract internal national security weaknesses.

In the report, the GAO listed a devastating series of security lapses going back to 2010, but we don’t even have to look that far in the past to see big problems.

In 2015, a judge sentenced Pedro Leonardo Mascheroni, who worked at Los Alamos National Laboratory, to five years in prison for attempting to sell nuclear secrets to Venezuela. (Specifically, he was caught attempting to sell the ability to make an electromagnetic pulse bomb.) The following year, Charles Harvey Eccleston, who worked for the Department of Energy, pleaded guilty to attempting to “compromise, exploit and damage U.S. government computer systems” with a spear-phishing attack and “sell information to a foreign intelligence service.”

The year after that, a judge sentenced Grigory Trosman, a DOE program manager, to eighteen months in prison for “accepting bribes in exchange for official acts” related to work in Eastern Europe. In 2021, nuclear engineer Jonathan Toebbe, who was affiliated with the National Nuclear Security Administration, and his wife, Diana, both pleaded guilty to sending classified material to an unnamed foreign power.

Those are government workers who were bad at selling secrets. (No list exists of the foreign assets who were good at selling our technology.) So what is going on at the DOE, and why does the GAO (and quite a few members of the intelligence community) think national laboratories specifically are a problem?

GOING BACK TO THE START

First, who owns what. Most national laboratories belong to the Department of Energy, though there are a couple of exceptions, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention laboratory and a handful of Defense Department-affiliated labs. Employees at those labs obtain a security clearance, generally, through the standard federal clearance process, typically overseen by the DOD or other designated federal agency.

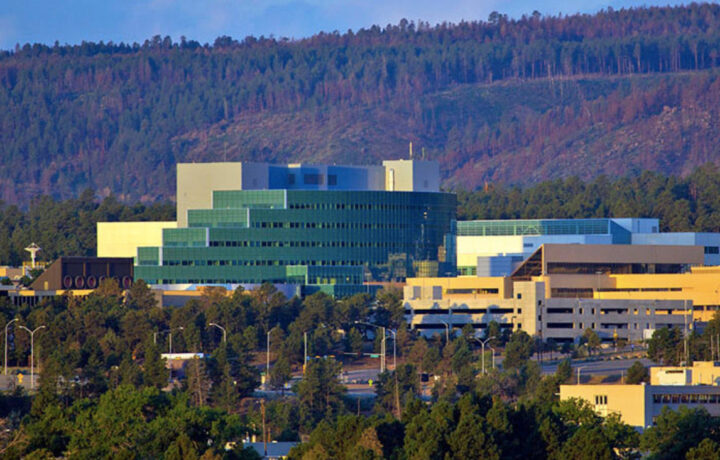

The DOE, however, has its own distinctive security clearance terms. This is in part because of history. Much of the secrecy apparatus of the United States can trace its roots to the Manhattan Project, which established not only the country’s first national laboratory, but also an effective model for large-scale, secret collaborations between government offices, universities, and the scientific community.

The post-World War II Intelligence Community and Defense Department would evolve their own byzantine systems in the decades that followed, and momentum would keep the DOE on its own trajectory. It’s one reason why DOE workers don’t get a secret clearance—they get an L. Instead of a Top Secret, they get a Q. And so on. Sure, nomenclature is a small thing, but the big differences branch off from there.

WHAT IS A NATIONAL LABORATORY?

We already have the Bomb, so what do national laboratories do these days, anyway? All sorts of things. You get in your Tesla to drive to work in the morning, and everything just sort of appeared one day without you noticing, and eventually engineers turned them into an amazing car. The lithium-ion battery, the advanced materials for electric motors, the underlying tech for the charging network—but all that stuff had to be researched across decades before companies could mature it for practical use.

You might recognize a few popular national laboratory successes. The Internet. Advanced genomics. Nuclear power. Lithium-ion batteries. Supercomputers. These are giant, civilization-shaping technologies, and your tax dollars at work. This is an important reason that we remain a superpower.

But let’s say you are not the wealthiest, most powerful country on Earth, but you want a great big boost in technology. Why spend all that time and money inventing advanced solar panel technology when you could just steal it?

Which is why the DOE and national laboratories specifically are hot spots for foreign espionage. The question in a sense isn’t why there are so many failures. The real question is why aren’t there more. (In fact, there definitely are—we just aren’t catching them.)

A DIFFERENT TYPE OF WORKER

National laboratories have another difference worth noting as well. You don’t accidentally find yourself applying to the CIA. You know exactly what you’re getting into, not only as a profession, but as a culture. You and everyone around you likely have the concept of secrecy at your cores. It’s one reason why—anecdotally, at least—CIA employees tend to marry CIA employees. (The Company actively encourages employees to marry each other.)

But if you came up in academia as a biochemistry researcher studying abstruse compounds with biofuel potential, or a gimlet-eyed nuclear physicist, you entire world and worldview is shaped by the free and open sharing of information. That’s the foundation of science, after all.

In other words, it’s a much shorter walk to the edge of the cliff for a national laboratory researcher than an intelligence analyst—and the entire world knows it. It’s not that scientists are less honorable; they just think and work differently. Unless DOE counterintelligence—and just as importantly today, its Insider Threat program—is on their game, our loss can be another nation’s quantum leap.