It has been seen in movies and TV shows for decades and commonly known as the lie detector, the polygraph test was recently in the news for its use on the reality series The Bachelorette, where five of the show’s suitors were strapped to the device. It didn’t take trained experts or even especially eagle eyed viewers to notice something was off.

The polygraph machine was hooked up to flashing red and green light bulbs, while a laptop screen reportedly showed a steady heartbeat. As numerous entertainment news websites including Screenrant noted, it wasn’t a lie detector at all, but rather was a lie put on by the show’s producers to intensify the drama. The faux polygraph proved nothing in the context of the reality series, but some psychologists would argue the same can be said of actual polygraph machines.

As the American Psychological Association noted, Leonard Saxe, PhD, has argued that the idea that such a machine could be used to detect a person’s veracity by monitoring psycho-physiological changes is more myth than reality. The instruments can’t actually detect a subject’s truthfulness, and instead the process requires that the person interviewing said subject must infer deception through analysis of physiological responses to a structured yet un-standardized series of questions.

The Three Indicators – How Polygraphs Work

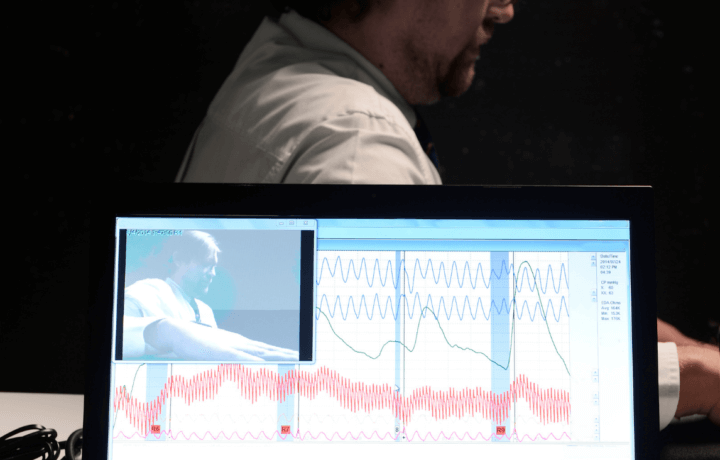

Unlike the machines seen in movies and TVs that have lights that signal when a person is lying, polygraphs work by assessing three indicators of autonomic arousal that include heart rate/blood pressure, respiration, and skin conductivity. The cardiovascular activity, including heart rate, is assessed by a blood pressure cuff, while rate and depth of respiration is measured by pneumographs placed around the subject’s chest. Skin conductivity is measured by electrodes attached to the subject’s fingertips.

However, this recording instrument and the accompanying questions – the parts that are most familiar in the world of fiction – are only part of a polygraph examination. There is also a pretest interview that is conducted to ensure that subjects understand the questions, but also to induce a subject’s concern about being deceptive.

The actual test doesn’t really measure deception or lying directly. But it provides the signs that could infer that the subject is attempting to deceive the interviewer. It is therefore critical that the information is used in conjunction with everything else that is known about that individual to provide a clearer picture of whether or not the subject is being truthful.

Canada Looks at Polygraph Reliability Issues

Because the test measures bodily responses, some argue that it isn’t impossible for the test subject to alter his/her bodily responses to interfere with the tests. This can include something as simple as taking medication to reduce anxiety, using an antiperspirant to reduce or prevent sweating, and even just biting parts of the mouth after each question to demonstrate a constant physiological response. To truly “beat” a polygraph and to conceal a true “lie” may require some training.

However, many argue the credibility of the machine in part because the technology turns 100 years old in 2021. Even when it was first introduced, its reliability was challenged, and over the years, those challenges have only increased. This month, the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency (NSIRA), Canada’s watchdog body that oversees the nation’s intelligence agencies, released a report that questioned the merits of polygraph tests. NSIRA’s report called out a lack of clear boundaries between the tests and medical analyses and also noted the limited oversight of the polygraph program.

The report suggested the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), Canada’s domestic intelligence agency, couldn’t justify the merits of the examiners to ask medical-related questions of subjects despite not being medical practitioners. Those who spoke to NSIRA on the condition of anonymity also described the negative impact that an unfavorable polygraph test had on their lives.

NSIRA is not the first to question the use of the polygraph in Canada. Its predecessor agency, the Security Intelligence Review Committee (SIRC) also called upon CSIS to stop using the tests in seven consecutive reports published from 1985 to 1992.

Despite the controversy over polygraphs, the tests likely aren’t going anyway anytime soon – and likely the media’s fabrications around the tests aren’t likely to get any more accurate. The best thing is to understand what you’re up against so you can prepare accordingly and of course, be truthful in your responses.