“The secret of a good sermon is to have a good beginning and a good ending; and to have the two as close together as possible.” ― George Burns

Few writers could tell a story like Norman MacLean. Entering the world two days before Christmas in 1902, MacLean was one of seven children born to his parents, John – a Presbyterian minister – and Clara. Growing up in the shadow of the Bitterroot Mountains in western Montana, Norman’s stories focused on the idyllic nostalgia of a youth spent in the valley of the Clark Fork river in Missoula, Montana. Most people who know his stories came to them through the 1992 Robert Redford film, A River Runs Through It.

But there was so much more to MacLean’s stories than could be captured in a two-hour sitting. His stories were about the lessons of life, and those lessons rarely end when the final credits roll. But one lesson in particular always stood out to me, enough so that I’ve probably cited that specific example more times than I remember.

For the better part of his youth, Norman MacLean’s education was provided by his father, who was – to put it mildly – a stickler for brevity. In the film version of A River Runs Through It, Robert Redford narrates the elder MacLean’s method of writing instruction: Write it again, half as long.

As a result, Norman MacLean’s readers always found tightly woven stories, where every word mattered. He didn’t use two words when one would do; he didn’t rely on flowery prose to convey an idea that could be simply expressed. He was a master of his craft and a genius with brevity.

For the Reverend John MacLean, it seems, brevity was next to godliness.

Churchill on Brevity

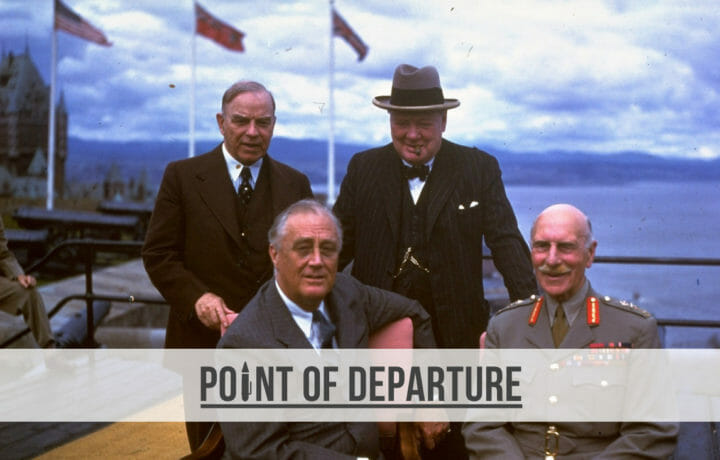

In the early days of the Second World War, with the Battle of Britain still raging over the skies over London, Prime Minister Winston Churchill issued a one-page memorandum to his staff pleading for brevity. “To do our work, we all have to read a mass of papers. Nearly all of them are far too long. This wastes time, while energy has to be spent in looking for the essential points,” Churchill wrote. “I ask my colleagues and their staffs to see to it that their reports are shorter.”

Facing an existential crisis is bad enough without spending an inordinate amount of time making sense of lengthy, senseless diatribes. “The discipline of setting out the real points concisely will prove an aid to clearer thinking,” Churchill noted.

Normally, you would expect that such advice would be well attended. However, during a 2013 review of documents in the British National Archives, researchers discovered that Churchill had issued another call for brevity in November 1951, citing his original memo in the process. “Official papers are too long and too diffuse,” Churchill noted in his letter, chiding staff for being long-winded and writing jargon-filled messages

The Three Bs of Brevity

The necessity for brevity was drilled into me early on in my professional career.

“Be brief, be brilliant, be gone,” intoned my senior maintenance warrant one day in his unmistakable east Tennessee drawl. I was preparing for the Logistics Readiness Council, the monthly division-level maintenance meeting chaired by the commanding general, and Chief Hunley was offering a dose of his trademark country wisdom. “Say what ya gotta say,” he said simply. “Make it count and get the hell out.” The more you talk, the longer others have to wait and the greater the chance you’ll say something that you have to explain later.

In the years since, the Three Bs have become central to my engagement style as a leader and fundamental to my philosophy. Brevity isn’t just about keeping your comments brief, it’s also about respecting others’ time. Just because you’re scheduled for a one-hour meeting doesn’t mean you have to talk for an entire hour. Make your point in as few words as possible. Time is a valuable resource and there’s only so much of it in a day.

Others will thank you for it.

The Brevity Code in Action

Several years ago, I stopped by the commanding general’s office to schedule an office call to update him on our progress on an ongoing initiative. “I only need about 15 minutes,” I told the scheduler. “I’ll go ahead and schedule you for an hour,” she replied. I must have given her the look, because she quickly added, “He likes to schedule you for a full hour. He knows you’ll only take ten minutes. But then you’ll have ten minutes to talk, and he’ll have forty minutes to catch up on other things after you leave.”

Develop a reputation for brevity and you might just find that more doors are open to you than might be otherwise.