Over the weekend, inside-the-beltway publication Axios revealed that Attorney General Jeff Sessions is considering requesting polygraphs for all employees of the National Security Council in an effort to find the leaker (or leakers) responsible for the unauthorized release of the transcript of President Trump’s early phone calls with world leaders. The report says that while Sessions is frustrated with all the leaks, he believes that the number of people who had access to the transcripts is small enough to make the polygraphs worthwhile, and “the idea that the President of the United States can’t have private conversations with foreign leaders was a bridge too far, even for Democrats.”

The Twitterverse predictably exploded with cries of “innocent until proven guilty” and “lie detector tests are scientifically invalid.” While both of those statements may well be true, they are nonetheless irrelevant.

polygraphs are routine for those with high level clearances

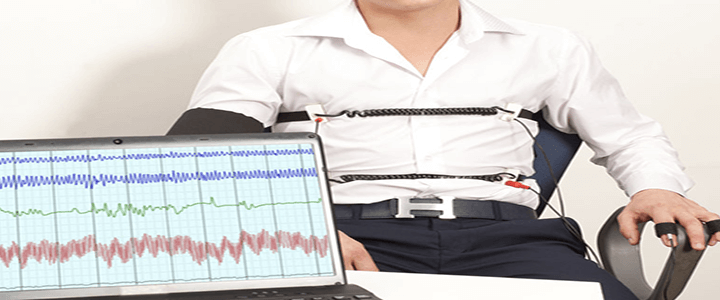

Use of the polygraph machine, which measures heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, skin conductivity, and “squirming” in the chair, is inadmissible in a criminal proceeding, but such use has been part of the screening process for granting high-level security clearances since the early days of the Cold War. If your job requires access to Special Access Program information — as the jobs in the NSC do — chances are, you’ve undergone a polygraph exam at some point.

But even those exempt from the normal investigation and adjudication procedures, which includes most of the NSC’s presidentially appointed employees, may still be subject to these exams.

The government employs three kinds of polygraph exams: the counterintelligence polygraph, which seeks to uncover espionage; the lifestyle polygraph, which probes topics such as drug and alcohol use, marital infidelity, or addictive and compulsive behavior; and the full scope polygraph, which combines the two. Presumably, Sessions wants to employ the CI polygraph in this case.

The tests are designed to detect deception by measuring physiological responses to questions and comparing them to answers given to control questions (Is your name John Smith? Is today Tuesday?) Four out of five dentists surveyed may recommend sugarless gum for their patients who chew gum, but the scientific community is more divided on the validity of polygraph exams and their value as a screening tool.

what is the polygraph’s utility?

In 2002, the National Academies recommended that “The federal government should not rely on polygraph examinations for screening prospective or current employees to identify spies or other national-security risks because the test results are too inaccurate when used this way.” However, relevant to the current situation, the study did concede that for “examinees… untrained in countermeasures, specific-incident polygraph tests can discriminate lying from truth telling at rates well above chance, though well below perfection.”

One solution to this problem was explored in an article published in the the journal of the American Polygraph Association (admittedly not an unbiased source) which argued that the answer is actually more testing. If there is a 9.3 percent chance that an innocent person would be falsely identified as guilty in a polygraph test, and the test were administered twice to the entire population, “the likelihood that an individual would fail both of the tests is only p = .093 * .093 = .0086.” In other words, the likelihood that an innocent person would fail a polygraph twice is less than one percent.

Furthermore, the article argues, if one merely uses the polygraph for narrowing the list of potential suspects to a more manageable number, then the polygraph has proved its usefulness.

One last point: as a friend who works in the intelligence community pointed out to me, the polygraph machine itself is often little more than a prop. The mere threat of using it elicits admissions, or at least exposes clearly deceptive behavior.

To catch the leakers who are weakening not just the current president but the presidency itself, I’d say it’s worth a shot.