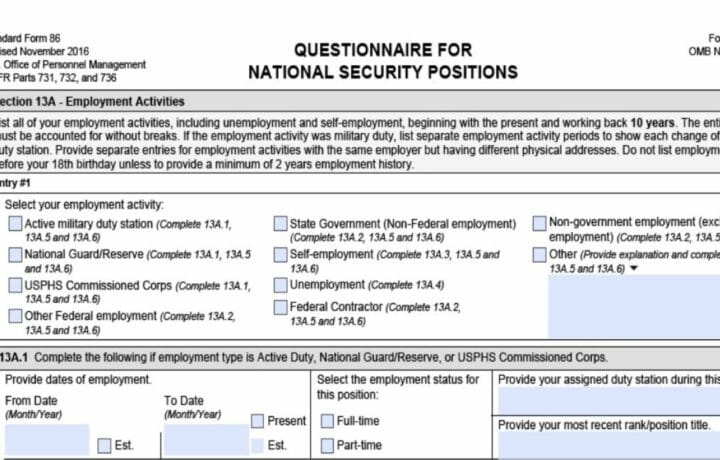

As I recently wrote about, the SF-86 can be a deceptively complicated form. It trips up plenty of smart people, so if you’ve found yourself realizing you made a mistake post-submission, you’re in good company.

There are two kinds of mistakes from a legal perspective: those that are material and those that aren’t. An immaterial mistake would be something like an outdated address for a reference or inadvertently listing a relative as a foreign national when they’ve actually been naturalized and renounced their foreign citizenship. Those types of mistakes should have no bearing on the government’s ability to conduct a background investigation or accurately assess whether you pose a security risk. Thus, they don’t raise an inference of intentional dishonesty by the applicant.

Material mistakes, on the other hand, are those that appear designed to paint the applicant in a more favorable light and increase the odds of successfully obtaining a clearance. These types of mistakes, even if perfectly innocent, can call into question your integrity and adversely prejudice the background investigation process.

Let’s assume for the purpose of this article that the mistake in question is a material one; for example, you checked “no” to the question about arrests within the last seven years, but subsequently realized that the misdemeanor shoplifting charge you thought was eight years ago was actually six years ago.

What separates those who get nailed for that mistake from those who don’t?

A prompt correction and a paper trail.

Unfortunately, many applicants in this position make the grave mistake of waiting until their meeting with a background investigator to correct the record. By that time, it is often too late. The investigator’s report will read that he or she “confronted” you with the discrepant information, and that can be detrimental to your prospects of a favorable clearance decision.

Other times, applicants will approach their security manager with the intent of making a correction to a recently submitted SF-86, only to be told that the security manager has already released the form to the investigating agency and nothing can be done. In that situation, don’t rely on a verbal conversation to protect yourself against a falsification claim. Instead, immediately create a paper trail by emailing the security manager, re-capping your conversation in writing, and clearly laying out the fact that you made an inadvertent mistake by providing the accurate information that should have been on the form. Print a copy of that email correspondence and keep it in safe place at home in the event that you need it after departing the service of that employer.

This may seem like obvious advice, but I’ve seen countless avoidable allegations of intentional dishonesty that the applicant later convincingly claims was an inadvertent mistake they tried to correct contemporaneously. The problem is that I’m not the one who requires convincing.

This article is intended as general information only and should not be construed as legal advice. Consult an attorney regarding your specific situation.